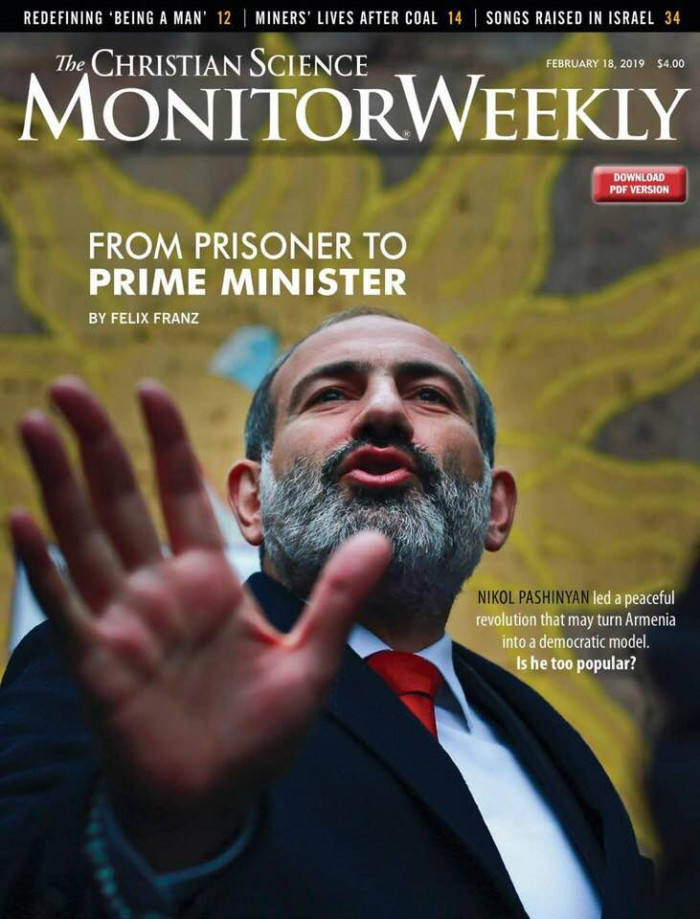

The Christian Science Monitor: "Peaceful revolutionary: Can Armenia’s prisoner-turned-prime minister govern?"

It may not be wise to lecture a judge about right and wrong, particularly if the judge is about to decide whether you should go back to prison. But Nikol Pashinyan, the leader of the Armenian revolution who abruptly and improbably became prime minister, has a history of taking bold actions. In 2008, after 10 people had died during political protests in the Armenian capital of Yerevan, the ruling party made Mr. Pashinyan a scapegoat for inciting “mass disorder” and sought to throw him in prison. He spent more than a year in hiding, occupying the top spot on the country’s most-wanted list. Eventually Pashinyan turned himself in when a general amnesty was announced for political prisoners. But despite meeting the requirements, Pashinyan’s name was conspicuously missing from the amnesty list.  The Christian Science Monitor: "Peaceful revolutionary: Can Armenia’s prisoner-turned-prime minister govern?" The fiery opposition leader protested his persecution. While presenting his case in court, he became distracted by a poster on the wall of the judge’s chambers. It displayed several Kalashnikov rifles, with descriptions and small pictures detailing the inner workings of the weapons. Pashinyan delivered a passionate lecture on how inappropriate a poster promoting assault rifles was for a judge’s office. His lawyer was aghast at his brazenness. In the end, the judge took the poster down and granted Pashinyan partial amnesty. His sentence was shortened, but he did serve almost two years in prison. The moment was vintage Pashinyan. To his opponents, he’s eccentric, reckless, and self-righteous. To supporters, he is principled and puts country and people before his own interests – always. There is one thing, however, both camps agree on: The man who headed a fairy-tale revolution that has put Armenia firmly on the path to becoming the world’s newest modern democracy is outrageously charismatic. For a few days in the spring of 2018, Armenia made headlines around the world. The tiny country in the southern Caucasus – uniquely wedged between Europe and Asia, the Middle East and Russia – staged an entirely peaceful revolution. Hundreds of thousands of people protested against government corruption and a power grab by then-Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan. The protests brought the country to a halt through joyous and highly organized civil disobedience. White confetti wafted through the streets instead of tear gas. The Economist declared Armenia, with a population of a mere 3 million, the 2018 “country of the year” for the nonviolent transition of power. While many independent groups joined the protests, one individual harnessed all the energy of the demonstrators, united the interests of urban and rural Armenians, and embodied the desires of young and old alike. That person built a coalition so strong that after just two weeks of mass demonstrations, Mr. Sargsyan stepped down with a remarkable mea culpa. “Nikol Pashinyan was right, I was wrong,” Sargsyan announced via an official statement on his government’s website. “The situation has several solutions, but I will not take any of them.... I am leaving office of the country’s leader, of prime minister. The street movement is against my tenure. I am fulfilling your demand.”  The Christian Science Monitor: "Peaceful revolutionary: Can Armenia’s prisoner-turned-prime minister govern?" Few expected Sargsyan, who had been ruling the country for a decade, to resign so quietly. But the style of his exit was a direct response to that of the man pushing him out the door. “Pashinyan has a combination of charisma and political acumen or street smarts that’s very rare, especially in former Soviet republics,” says political analyst Richard Giragosian, who leads an independent think tank in Yerevan. The journalist, revolutionary, and opposition leader became prime minister last May. Now he faces his hardest task yet: governing. History brims with figures who rode the zeal and idealistic fervor of revolutions to power – from Nelson Mandela in South Africa to electrician Lech Walesa in 1980s Poland to Vaclav Havel, the poet laureate of the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, after which Pashinyan, artfully, named Armenia’s peaceful revolt. Some of those leaders were more successful than others. One lesson of street revolutions is that people expect improvements quickly. Many critics doubt Pashinyan can unite this still-fragile nation, which faces ever-present tensions with neighbors and the always awkward relationship with Russia. But others believe he has the vision and instinctual skill to bring real, long-lasting change to Armenia – and might make the country a model for other former Soviet countries struggling to navigate the transition to a modern democracy. Charisma is a divine gift, according to its Greek root, which literally translates to “gift of grace.” Science continues to search in vain to quantify exactly what “it” is, but there’s little doubt that you either have it or you don’t. Nikol Pashinyan has it. If you talk to people who know him, it is the one characteristic that is always mentioned. Take Hayk Gevorgyan. The journalist and part-time farmer first met Pashinyan in 1994, when the two worked together on a newspaper. Mr. Gevorgyan says he was impressed by Pashinyan’s passion about a citizen’s right to criticize the government. This was just a few years after the fall of the Soviet Union, so questioning authorities was still a relatively new freedom. “Nikol gave trainings to other journalists in his free time,” Gevorgyan says. “He was the first one to teach people to doubt.” Pashinyan was barely 20 years old then. After four years, Pashinyan decided to found his own newspaper, The Daily. Gevorgyan followed him because, he says, “I knew he was going to do important things, so I wanted to keep on working with him.” During the parliamentary elections in 1999, The Daily was sharply critical of the government and was fined for libel. The paper refused to pay. The government confiscated The Daily’s equipment and froze its bank account. Pashinyan was convicted and sentenced to a one-year suspended sentence. As soon as the court case was settled, the same team behind The Daily – including Pashinyan’s wife, Anna Hakobyan, who is also a journalist – acquired the license of another newspaper, the Armenian Times, which was struggling at the time. In the following years the Times’s readership continuously grew. By 2007 it had become one of the country’s most successful and highly regarded papers. It was in the early days of the Armenian Times that Pashinyan dropped a thick folder on Gevorgyan’s desk and asked him to write an article on the contents. It was the national budget. An engineer by training, Gevorgyan was a general assignment reporter who had no deep knowledge of economics. But he pulled off the assignment and eventually became economics editor. He laughs and says that if Pashinyan had asked him to cover biology, he would probably be science editor today. “I trust Pashinyan more than myself,” he says.  The Christian Science Monitor: "Peaceful revolutionary: Can Armenia’s prisoner-turned-prime minister govern?" Others agree that he has the ability to relate to and embolden people. “He satisfies the part of Armenian society that wants to love their leader,” says Maria Karapetyan, who was recently elected to the new parliament. She says Pashinyan cites poems in his parliamentary speeches, and when a supporter gives him a tie as a gift, he “immediately puts it on, no matter how ugly it may be. He knows how to make people feel important.” For now, Armenia remains in a collective frenzy over the peaceful revolution, and Pashinyan is enjoying an extended honeymoon as leader. His newly founded party alliance, My Step, won a landslide 70.4 percent of the vote in the parliamentary elections in December. But the adoration of him has moved beyond political support and developed into what some critics call a cult of personality that could undermine the very ideals behind the Velvet Revolution. The image of “our beloved prime minister,” as many Armenians refer to Pashinyan in casual conversations, now graces iPhone cases, T-shirts, and even fingernail extensions. He is depicted alternately as a Christian saint and a Roman emperor. “I think there is a fine line between merchandise and personalty cult, and I believe this line has been crossed,“ says Ruben Muradyan, an information- technology worker in Yerevan who has curated a collection of fan articles about Pashinyan on Facebook. The prime minister has pledged to reject the authoritarianism of the past and move toward liberal democracy, but some Armenians, like Mr. Muradyan, worry that too much hope is being placed in a single man. During a press conference right after his election victory in December, Pashinyan was asked whether he sees his personal glorification as a problem. He laughed off the question saying, “Many people in the streets want a selfie with me, and I can’t refuse them just not to endanger our democracy in Armenia.” Muradyan believes that Pashinyan has good intentions but lacks the necessary education to lead a country. “He doesn’t understand why a personalty cult can be dangerous, and that’s very worrying,” he says. *** Pashinyan was born in 1975 in Ijevan, a small city of 21,000 nestled at the foot of the forested Gugark Mountains two hours north of Yerevan. His mother died when he was 12 years old, and his father, a football and volleyball coach, quickly remarried.

He then left rural Armenia to study journalism in the capital at Yerevan State University, where he continued to crusade for change and to pinprick authorities. Just days before his graduation, Pashinyan was expelled from YSU without a degree. After a meeting with the university’s vice president, Pashinyan declared that his dismissal was the result of a critical article he had written about the sister of the dean of the university. The official explanation was that he had missed too many days of school. Part of Pashinyan’s appeal today is a gritty authenticity rooted in his rural upbringing. In a TV report from 2016, you can see Pashinyan in a garden – he was an opposition politician in parliament at the time – skinning a pig with his brother surrounded by the snow-shod hills of his hometown. He speaks to an interviewer while skillfully burning the surface of the dead animal with a small flamethrower. None of it feels staged. It’s as if Pashinyan was giving a TV reporter a tour of where he grew up and his brother happened to need help with a task they had done together countless times. After Pashinyan became prime minister, he and his family moved into the state’s official residence. In an attempt to keep his promise of being more transparent, he gave a video tour of his new home with his cellphone and streamed it on his personal Facebook page. The house is spacious and comes with a sauna, pool table, and large garden. A few weeks after the move, Pashinyan and his wife gave their old apartment to a family in need. A single mother moved in with her children. The gesture was indicative of Pashinyan’s skill at appealing to different audiences. He has established a name with the urban elite through his work in journalism and parliament for the past 25 years, but he can just as easily connect with rural Armenians. In March 2018 he started his demonstration campaign against the former prime minister’s power grab with a 125-mile march from Gyumri, Armenia’s second largest city, to the capital. The campaign was a way to engage people in villages and regions that have long felt ignored by Yerevan. “[It] gave them more of a voice, more of a choice in politics ... in other words, tapping into an ignored constituency,” says Mr. Giragosian, the political analyst. During the march Pashinyan grew a salt-and-pepper beard and wore a camouflage T-shirt and a baseball cap. It was part of an image makeover to further distinguish him from the political elite in the capital and, some argue, to disguise his lack of military experience.

“For decades Armenia has been in a state-of-siege mentality,” Giragosian says. “I think [his lack of military experience] is one of his biggest weaknesses.” What Pashinyan lacks in military experience he makes up for with a record of conflict-laden street politics. He was jailed for political actions multiple times, and in 2004 his car was blown up in front of his newspaper’s office, allegedly in an attempt to intimidate him. A local journalist said she met a taxi driver last summer who knew Pashinyan from his time in prison. They had been in the same cellblock. He remembered Pashinyan was always reading, saying he had a plan and that he needed to keep his mind fresh. He was well-liked there, the former fellow inmate recounted. In 2010 Pashinyan became the first jailed candidate in independent Armenia’s history to run for parliament, underscoring his tenacity and resolve. He was released from prison in May 2011 and was elected to the legislative chamber in 2012. A year later he founded his own party, taking the final step away from his career in journalism and committing to politics. A fiery orator, he was the most outspoken opposition politician in parliament, always inveighing against people he opposed and trying to hold the government accountable. Yet having a stronger opposition in parliament wasn’t enough to safeguard Armenia’s young democracy from authoritarian tricks. After serving two consecutive terms as president, Sargsyan shifted most political power from the president’s office to that of the prime minister and then claimed the office for himself. What he didn’t expect was that his brazen maneuver would alter the mood of the country. Many Armenians felt the nation was in danger of becoming a corrupt one-party state. Pashinyan was waiting with tinder to fuel a populist spark. “Pashinyan had a much better sense of the pulse of Armenia and a much more accurate reading of the temperature of the country,” Giragosian says. He remembers that neither the government nor outside experts thought mobilizing people on this issue would be possible. “The critical mistake the government made was underestimating Pashinyan,” Giragosian says. Within a few weeks, discontent turned into open dissent. Since the early 2000s, waves of civic protest have swept Armenia every few years. The biggest demonstrations happened around alleged electoral fraud during the presidential election in 2008 and over a 17 percent hike in electricity rates in 2015. Both times saw violent clashes between protesters and police. The demonstrations in 2018 were different. When it became clear that Sargsyan didn’t intend to leave power, several groups started preparing for a new round of dissent. Pashinyan and his opposition party were only the most prominent force. Drawing inspiration from Nelson Mandela, the Vietnam antiwar movement, and Mahatma Gandhi, Pashinyan and other civil society groups promoted a no-violence strategy. “We were told to literally turn the other cheek when we are attacked by the police,“ says Karo Ghukasyan, a young activist who worked closely with Pashinyan. One of the movement’s tactics was to disrupt traffic without breaking the law. Over Facebook, Pashinyan asked people to block roads. Small groups of protesters took turns crossing the street in so-called infinity loops, making it impossible for cars to proceed. At the height of the protests, on April 16, demonstrators blocked all bridges and paralyzed the city’s entire subway system. People had massive picnics, danced, and sang in the streets of Yerevan. An Armenian at the time described the mood in the country as the “happiest apocalypse in the world.” *** Almost a year later, the atmosphere in the country is still hopeful. But weaknesses in the new government are also apparent. Pashinyan is a loyal person: He has brought many people he learned to trust over the years with him to government. “He gathered politicians of his kind around him. He is never surrounded by professionals,” the IT expert Muradyan complains. Political analyst Giragosian partially agrees. He sees too little expertise in Pashinyan’s cabinet, especially when it comes to economic matters. But, he notes, Pashinyan has demonstrated a willingness to ask for help. He tells the story of a woman who contacted Pashinyan after the revolution offering her expertise. She had left Armenia with her family as a child and specialized in civil aviation in Denmark. Pashinyan invited her to Armenia for a face-to-face meeting. Not long after, he appointed her the new head of the country’s civil aviation agency. Now she is instituting sweeping reforms, including bringing in low-cost air carriers and developing Armenia as a transit hub. Politically Pashinyan is often described as a centrist, a business-friendly liberal. The prime minister himself, like many politicians, eschews labels. At a press conference for international media after his election he said: “There are no clear lines between political ideologies anymore.... In the 21st century, those lines disappeared.” He’d rather be labeled only as “pro-Armenian,” he says. Pashinyan’s recurring theme in more than two decades of political engagement is his fight for democracy. Ms. Karapetyan, the newly elected member of parliament, says that she and Pashinyan, both members of the same party, want to see a transition of power through elections in the near future. “You can never say you’re a true democracy if you don’t have that,” she says. Still, countless challenges loom on the horizon. For more than a decade, the former government had glossed over serious domestic problems. “Anything you touch here with new legislation is a mine that can potentially explode,” says Karapetyan. And foreign policy challenges are just as daunting. Two of Armenia’s four borders are permanently closed, and trade with one of its southern neighbors, Iran, is becoming more difficult after US President Trump renewed sanctions. The conflict over disputed territory with Azerbaijan might flare up at any moment, and Armenia is still heavily dependent on Russia for trade and security. “Russia may come at some point and say, ‘Stop. We want to remind you of the limits of what you can do here [in establishing a democracy] in Armenia.’ And that’s a challenge,” Giragosian says. In the end, a lot hinges on Pashinyan’s ability to grow in office without overestimating his own capabilities. Giragosian, for one, is cautiously optimistic. He tells the story of how he was supposed to act as translator in a meeting between Pashinyan and the Swedish ambassador. But suddenly Pashinyan started talking in English; he had secretly taught himself. “He knows what he doesn’t know and recognizes the need to deepen his knowledge in areas where he is weaker,” Giragosian says. “That’s a very important quality.” |